Designing Accessible Cities and Making Walkable Cities

Dr. Abhijit Lokre

December 3, 2020

In India, city after city is focusing on making motorised vehicles the prime focus of transport infrastructure investment. Congestion is deemed undesirable and cities have declared war on it. Road widening, new roads, flyovers and multi storied parking lots are touted as the panacea for our urban transport woes. Ahmedabad has recently approved seven more flyovers. The SG road is being widened to six lanes with grade separation at all intersections. Mumbai is going ahead with a coastal road and Bengaluru is pushing for an elevated steel road. Municipal engineers and traffic police are interested in ‘clearing’ roads of traffic in the shortest possible time.

Cities are also investing in public transport. BRTS, metro, monorail, electric buses now dot the urban landscape. There is discussion on investment in hyperloops, metro lite, and similar ideas. Smart cities have infused funds in technology solutions to make our cities liveable. CCTV cameras, Automatic Number Plate Recognition (ANPR), ITMS are part of Central Command Centres (CCC) in many cities.

Mobility vs Accessibility – How far or how many?

Currently, most of the investment in urban transport is for mobility – even in public transport. Thirteen years after the NUTP stated that the focus should be on moving people and not vehicles, the focus firmly remains on moving vehicles. Good examples of moving people and redistributing road space equitably to all road uses are rare. A cursory reading of municipal budgets shows the skew in fund allocation.

Decision makers, traffic engineers and transport planners need to first get the distinction between mobility and accessibility.

Mobility is how far you can go in a given amount of time. Accessibility is how much you can get to in that time. (www.strongtowns.org)

The point of travel isn't to cover ground. It is to get us to the things we want to do. It is to get us to our jobs, our friends and families, recreation, and daily needs. Mobility focuses on connecting two points in the fastest way possible. On the other hand, accessibility focuses on how many places could be reached in the shortest time possible. This distinction is at the heart of sustainable planning principles. A mobility focused approach leads us to cities with dispersed land uses and a need to travel long distances. An accessibility focused approach leads us to cities with mixed land uses and most needs within short distances. It leads to finding solutions for activities such as walking and cycling.

Historically, Indian cities were always ‘accessible’ cities. As cities expanded, the focus shifted to mobility. Go to any Indian city today – flyovers are ubiquitous, an elevated road running through the city centre is common and technology to enable mobility is popular. Transport plans in our cities are called “Comprehensive Mobility Plans” – not “Accessibility Plans”. They focus on road network planning, parking solutions, public transport plans, freight, and logistics. They detail out solutions for better mobility along with estimated costs. They talk of accessibility – if at all – sparingly.

What has this meant for accessibility? As more mobility options get built, accessibility suffers. Trip lengths and trip times increase. The best BRTS in the country – the Ahmedabad BRTS – focuses on moving buses from station to station swiftly. Ridership has stagnated at 150,000 for the last five years, even as commuters call for better accessibility options to reach homes and workplaces from the BRT stations. Delhi’s metro system has some stations with abysmal pedestrian access. Mobility solutions end at the station. Commuters need to figure out accessibility.

Compromising on Safety

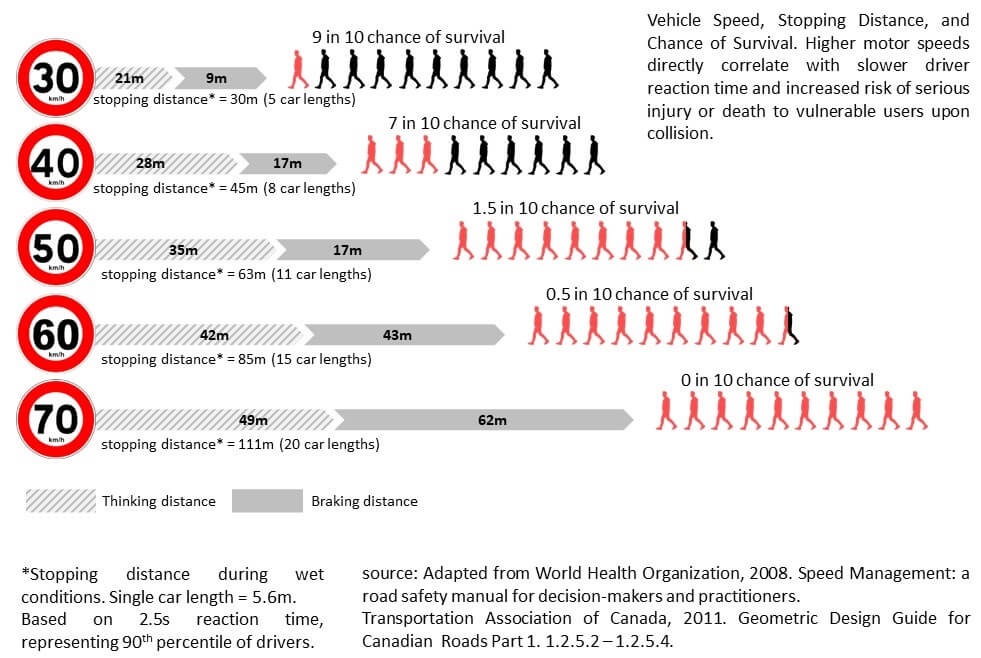

The high focus on mobility brings road safety issues. Fatal accidents in Ahmedabad increased from 200 in 2010 to 350 in 2019. Fifty percent of the people killed are pedestrians. Flyovers mean vehicles speeds have increased. High speed is inversely proportional to road safety as seen in the figure below. As speeds increase beyond 40 kmph, the chances of survival decrease dramatically.

Speed vs safety

Source: Adapted from WHO

Addition of pedestrian crossings is seen as an impediment to motorised vehicles. Foot-over bridges are proposed on busy roads as a ‘safe solution’ for pedestrians. Experience suggests that these foot-over bridges are grossly under utilised. They are, in fact, constructed to ensure that vehicles move faster. However, pedestrians prefer crossing at-grade. The image below shows just one pedestrian crossing on the bridge while the rest cross at-grade in the face of oncoming traffic.

Pedestrian crossings

Making a Difference

Some cities have recognised the need to look at accessibility along with mobility. Pune and Mumbai have come out with a ‘pedestrian policy’, which prioritizes pedestrians over vehicles. A dedicated NMT cell nests within the Pune Municipal Corporation headed by an executive engineer. PMC has also hired urban designers to help engineers design streets and public spaces. Several kms of arterial streets are being redesigned to achieve a better balance between accessibility and mobility.

Accessible streets in Pune

Source: ITDP

Chennai has come up with an ambitious plan to revamp over 100 km of its streets. This includes planning and designing street networks in neighbourhoods for accessibility. Coimbatore plans to emulate Chennai. Ahmedabad has begun work to redesign key arterial streets to expand space for pedestrians and slow down motorised traffic through tight turning radius.

Reducing speed through tight turning radius: CG Road Ahmedabad

Source: The Urban Lab, 2019

Kochi is redesigning its arterial streets to ensure a better balance between pedestrians and vehicles. Cities are investing in small urban design solutions to encourage high quality pedestrian facilities.

Public Bicycle Sharing (PBS) has emerged as another alternative for accessibility and last mile feeder for public transport. More than fifteen cities in India have installed PBS with varying degrees of success. These systems provide commuters with options for short trips and for last mile connectivity.

However, much more needs to be done. Discussions about accessibility and walkability need to be mainstreamed in the development process of cities. Urban local bodies need to address accessibility issues by developing visions and policies that support accessibility. They need to follow it up by allotting substantial funds in their budgets for building walking infrastructure and maintaining it. Municipal engineers and traffic police need to be sensitized about the need to take care of pedestrians and cyclists for ensuring their safety.

In the end, as citizens, we need to be clear about the city we aspire for – a ‘mobility’ city with infrastructure for vehicles or an ‘accessible’ city that prioritizes human beings.

Bhuj shows the way!

Dr. Abhijit Lokre

December 4, 2022

Introduction

In January 2001, Bhuj suffered major damage in an earthquake. More than 15,000 people were killed in the state and Bhuj was one of the worst affected towns. The walled city – the economic heart of Bhuj – suffered more than 70 per cent damage.

In the next five years, Bhuj was back on its feet. A Development Plan (DP) and eight Town Planning Schemes (TPS) ensured that the reconstruction was systematically done. The state government supported through grants, and loans from the ADB and other funding agencies ensured that infrastructure was upgraded.

What was remarkable about the reconstruction of Bhuj was the active role played by its citizens. Even with the damage caused by the earthquake and dealing with personal and income loss, the people of Bhuj participated in the planning through stakeholder consultations and close interaction with the planning authority. NGOs in Bhuj formed a group called Kutch Navnirman Abhiyaan to articulate people issues and represent them to the authorities. Public participation was at the heart of the process to bring back Bhuj to life.

Twenty years later, Bhuj continues to show the way!

The mobility plan

At The Urban Lab, we were invited in 2021 to work with Homes in the City (HIC) to prepare a mobility plan for Bhuj. Like any other Indian city, Bhuj faced multiple mobility and accessibility issues. HIC was keen on exploring what could be done to improve mobility in Bhuj – with a focus on the urban poor. While, they were interested in getting the ‘technical things’ right, they were not interested in just another mobility plan.

At The Urban Lab, based on our experience of preparing technical solutions to planning and design issues, and then watching them either not get implemented or get implemented in a completely different way, this was an opportunity to approach the problem in a different way. It was an opportunity to engage with people and through their stories and feedback, look at mobility from a human lens. These stories could then be used with data to paint a picture of what could be.

We began work in the winter of 2021, amidst the rise and fall of the COVID-19 pandemic. HIC organised multiple Focus Group Discussions (FGD) with various stakeholders. Over several visits to Bhuj, we interacted with school girls, housewives, auto rickshaw drivers, street vendors and the traffic police. We asked them to share their stories about mobility and accessibility in Bhuj. We met the erstwhile bus operator to understand why he had to stop the bus service. We conducted a survey of several schools with HIC’s support to understand students’ experience of accessing their school. Similarly, we conducted a survey in the slums to understand their experience of moving in Bhuj. Along with the qualitative aspect of the study, we also conducted several surveys to identify parking, congestion and shared auto routes in Bhuj. The result was a different kind of mobility plan. The plan document did not use modelling to predict future scenarios. Nor did it use numbers or codes to identify infrastructure projects. For example, a key solution demanded by the people and substantiated by vehicle counts and data from the DP was to restart the public bus service.

In early 2022, HIC got together a diverse group of people to discuss the final output of the mobility plan. The discussions were open and frank with participants ranging from street vendors, auto rickshaw drivers, school teachers, bus operator, NGOs and representatives from the Bhuj Nagarpalika. Sometimes, the discussions were heated. However, through it all, what was discernible was a genuine commitment to listen to all and take the discussion forward. The discussion concluded with a resolution to form a citizens group to identify key proposals that could be developed further and taken to the Bhuj Nagarpalika for further development.

Taking the mobility plan further

Two proposals that stakeholders were interested in were restarting bus services and redesigning the main street in front of the bus terminal to accommodate street vendors.

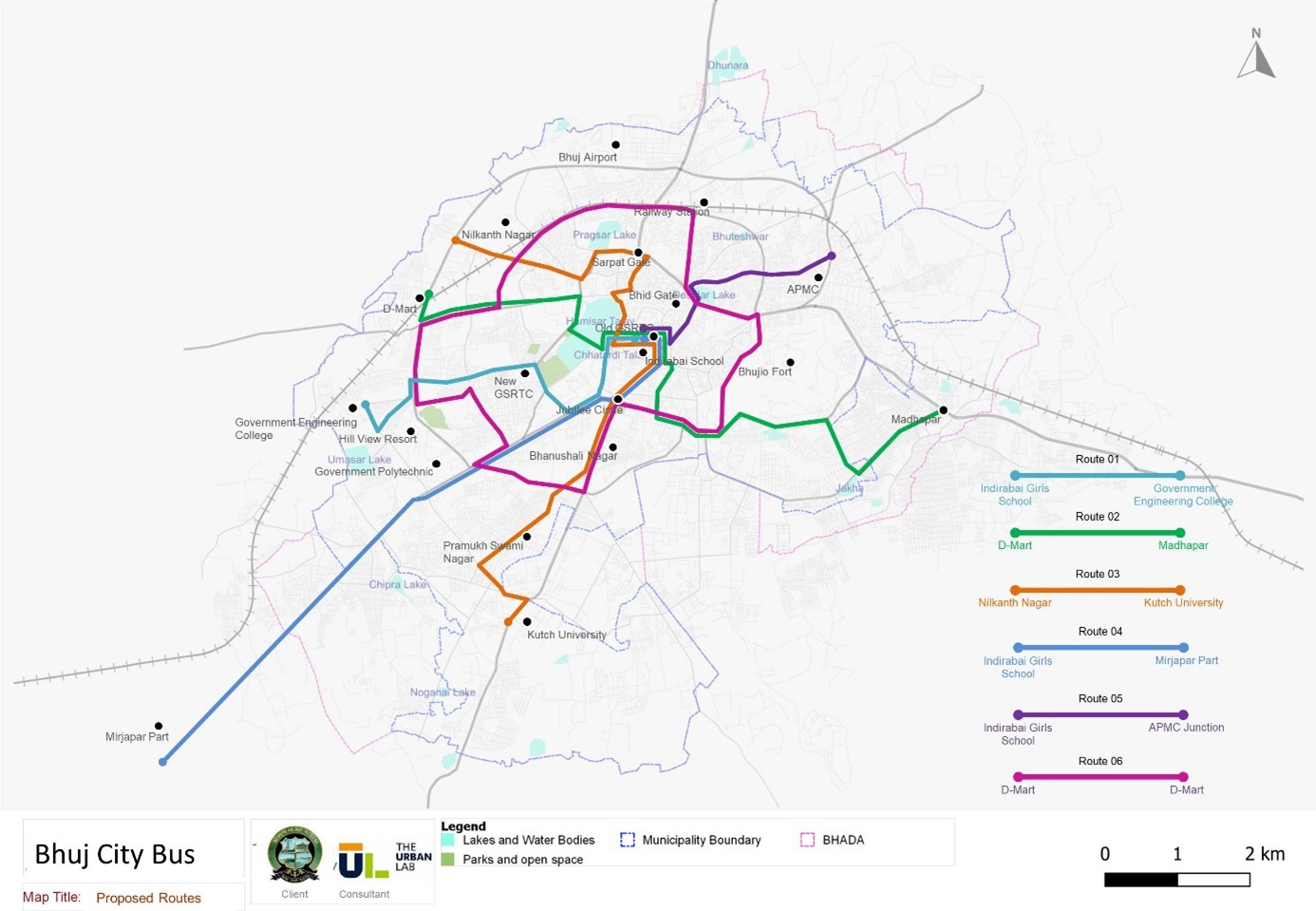

Bhuj Nagarpalika requested us to help them in preparing a DPR for urban bus operations that they could submit to the state government for funding under the Gujarat Chief Minister Urban Bus Service Scheme. Under this scheme, the state would fund 50% of the operations cost under a PPP scheme, subject to a maximum of INR 12.5 per km. Based on our knowledge of the city, predominant origins and destinations, and several interactions with the old bus operator and Bhuj Nagarpalika, we identified six routes operating at frequencies ranging between 20 – 30 minutes. A total of 25 buses were required for operations. The total grant requested from the state government was INR 9 crore over a period of five years, with the Nagarpalika matching it with an equal amount. The proposal was submitted in May 2022. The state government is expected to approve the proposal soon.

Six routes identified in Bhuj with a ring and radial pattern connecting the city centre with industrial estates, schools and colleges, hospitals, markets and transit hubs. The ring binds the network and allows passengers to move to destinations outside the city centre directly. Routes have overlaps to help passengers transfer. Integrated ticketing is proposed which would eliminate the need to purchase additional ticket when changing buses.

For the second proposal, TUL and HIC worked extensively with street vendors on the bus station road to redesign the street. Since this street also has bus movement, traffic movement also had to be kept in mind. The team made several site visits at different times of the day to map the street usage. Based on these inputs, the team prepared few design options, printed them and put them up on the street itself to get direct inputs from vendors. This interaction proved to be immensely useful – for us as well as stakeholders. We got direct inputs and stakeholders could visualise the street, while standing on the street itself. They got a sense of how the street would look like post development. Officers from the Bhuj Nagarpalika also visited the street to check the drawings and gave inputs.

Early morning scene at the street side vegetable market. The vendors organise themselves neatly with space in between for customers to move. Many of them do not have carts and spread their wares on the ground. These vendors will vacate their spots after 9 am leaving the area free for pedestrians and parking.

The TUL team explains the proposed design to vendors. These kind of exercises help stakeholders visualise the design and how their business would be influenced. It also provides the design team an opportunity to take feedback on ground and incorporate in their design.

The next step for TUL and HIC is to work with the Bhuj Nagarpalika and do a demonstration project through tactical urbanism to test the design and make changes based on the feedback.

What did Bhuj get right?

In the last 8 months of our involvement in Bhuj, we realised what a difference listening to people makes. As planners with years of experience, we thought we know it all. Most planners approach urban issues like this. Bhuj changed our perception. People who stay in Bhuj, who live, work, study and socialize there, have to be heard.

What Bhuj got right in 2001 was listening to its citizens! It continues to show the way.